Sorry, no katanas allowed

Just kidding, you’ll probably see something that looks like a katana a few paragraphs below. But let’s all agree that when people think of “Asian swords” they usually picture a katana in their minds—maybe even considering both terms to be equal. And I get it, katanas are cool, samurais are cool, and Highlander is cool (really, go watch it). But Asia is not just Japan, and every country, every nation, and every culture has its own swords. Given that my area of expertise is Chinese martial arts, I want to talk a bit about Chinese swords, their different types, a bit about their history, and how they are used. This is of course a general introduction to the subject, hopefully, some of the links will guide you, dear reader, to do your own research.

Two main types

First thing first. There are two basic types of Chinese swords: double-edged straight swords called jian (剑 pron. chee-en) and single-edged swords called dao (刀 pron. tao). Dao is generally, but not always, curved, similar to a sabre or a broadsword. There are single- and double-handed versions of both, and they both come in various shapes and sizes. The term dao is used for any single-edged blade, and that includes the common kitchen knife. Because of that, a lot of weapons have dao in their name, from small blades to big, long-handled polearms. I’ll get into more of that later.

Apart from shape and name, jian and dao differ in their use. Nowadays the Jian is a faster and subtler weapon. They are used to make precise cuts—mainly with the part of the blade that’s farthest from the hilt—and for stabbing. They are also weapons with a more mystical aspect, used by Daoist priests and generally regarded as “a hero’s weapon”. The dao resembles a machete a bit, and is used for chopping and hacking at the enemy with broad movements—less precise, but not less lethal.

A brief history

Early swords

Swords have been around since ancient times. I’m not a historian (so don’t quote me on this!) but as far as I’ve read, swords are somewhat related to spears. In a way, they are the polar opposite of spears: a long blade on a short shaft.

The earliest Chinese swords found were jian. Bronze jian appeared during the Western Zhou, and their blades were a mere 28–46 cm long (11–18 inches). These short stabbing weapons were used as a last resort when all other options had failed. Spears and dagger-axes were the preferred weapons in those times.

The jian‘s popularity gradually grew among soldiers. It’s a shorter weapon, easier to carry around, and leaves one hand free for other uses, such as carrying a shield. Around 500 BC, blades were longer, and the sword-and-shield combination became the favored tactic. By this time most swords were made of iron or steel. Jian length continued to grow, surpassing 100 cm (40in). Archaeologists found Han dynasty swords measuring 146cm (57.5in). These were huge, two-handed weapons, a bit impractical and given their length and their reduced durability. A stark contrast to the modern single-handed jian!

Enter the dao

Dao swords became widespread as a cavalry weapon during the Han era. They had the advantage of being single-edged, which meant the dull side  could be thickened to strengthen the sword, making it less prone to breaking. When paired with a shield, the dao made for a practical replacement of the jian, and so it became the more popular choice as time went by. Early dao swords were not that different from the jian of the same period. They had very similar length and straight blades.

could be thickened to strengthen the sword, making it less prone to breaking. When paired with a shield, the dao made for a practical replacement of the jian, and so it became the more popular choice as time went by. Early dao swords were not that different from the jian of the same period. They had very similar length and straight blades.

Further changes

As time went by and warfare evolved, so did the swords. The dao swords were very popular during the Tang dynasty, not only among the soldiers but as a ceremonial weapon in court, with several new types with varying shapes and lengths appearing. In subsequent eras, the shape of the dao changed, probably influenced by cultures of the steppes and Turkic peoples that used more curved blades. Both the dao and jian became shorter in length, the former remaining a weapon favored by soldiers, the latter mainly relegated to high-ranking officials and nobles. The latest periods of Chinese history—the Ming and Qing dynasties and the Republic—exploded with new styles of martial arts, and with them new types of swords as well. Long, short, one-handed, two-handed, used in pairs, and even some definitely odd-looking ones.

Swords or polearms?

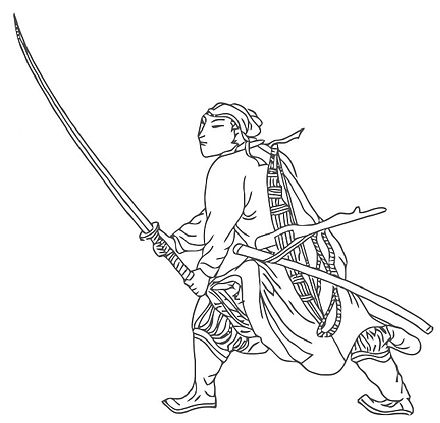

I would argue that most martial arts enthusiasts would know the Japanese naginata. Some probably might know the guan dao. And if you read my other article on Chinese weapons you know the podao. But not many are familiar with the zhanmadao (literally, “horse-chopping sabre”) and the chang dao (long sabre). You can find some version of the zhanmadao in many styles, some looking very similar to a podao. But the chang dao is harder to find. The Ma family Tongbei system and some northern styles like Xinyi Liuhe Quan and Piguaquan train with this long sword, nowadays known as miao dao (sprout sabre). It’s a very long two-handed sabre with a blade that has a blunt section or secondary grip near the hilt. The secondary grip gives it a more polearm-like use, which to me makes the miao dao a very versatile weapon.

But the two-handed grip is not a privilege of the dao. The shuang shou jian (two-handed sword), as the name suggests, is the longer cousin to the traditional single-handed jian. Nowadays this jian is mostly seen in several branches of Tanglangquan (aka mantis-style boxing) and modern Wushu. There is evidence of an older shuangshou jian in the Wubei zhi. But if this is directly descended from the earlier big swords or a more modern invention, I haven’t really found out. Judging from form videos, both the shuangshou jian and the miao dao are very fast weapons. And in particular the former shares some of the precision striking of the regular jian. The longer blade allows the wearer to attack and block or parry from a slightly greater, and therefore safer, distance.

Paired swords

If one weapon is good, why not use two of them, am I right?! So let us close this overview of traditional Chinese swords with paired ones. First the basics, namely the double dao and the double jian. This might seem like a no-brainer, but there’s a twist: a single scabbard will hold the pair. Each hilt and guard are halved, and so a fighter can use both as one and surprise the enemy by effectively duplicating their weapon. Double jian also tend to be shorter than single ones. Nowadays these are very popular weapons for demonstrations, but you can find older versions from the time people actually fought with weapons. Their origin probably lies in civilian fighters during the Qing dynasty.

One of my personal favorites is the hudie dao (butterfly swords). These are very large knives mostly used in pairs. They are a staple weapon of southern Chinese styles, from Wing Chun to Hung Gar to Choy Lee Fut, Pak Mei, etc. Some versions are pointier than others, but the shape is generally very similar. As I said they’re generally used in pairs, but some styles also have a form that uses one knife in one hand and a shield on the other. You can find more about their origins and history here.

Last but not least, the hook swords or tiger hook swords. As you can see on the left they look very cool. Technically dao because the long blade has a single edge. But also they have hooks, the crescent moon handguard is sharp and the bottom end is a short dagger. Their origin is a bit of a mystery, but they are likely an invention from the Qing era. Hook sword forms or routines typically involve linking both by the hook and swinging them like a whip.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this brief stroll through the world of Chinese swords. You can leave questions or suggestions in the comments section below. If, like me, you practice Chinese martial arts, ask your Sifu about some of these weapons. I’m sure they’ll have some interesting stories. As always, thanks for reading.

- Hidden applications in traditional martial arts - October 30, 2023

- The Kung Fu in Kung Fu Hustle (part 2) - November 1, 2022

- The Kung Fu in Kung Fu Hustle (Part 1) - October 5, 2022

Leave a Reply